From Vineyard to Grape Harvest

THE GRAPE HARVEST or AUTUMN

Francisco de Goya (1746-1828)

1786-1787

Museo del Prado, Madrid, Spain

Upon his arrival in Madrid in 1774 – and up until 1792 – Francisco de Goya designed tapestries for royal palaces. The work was unrewarding, as the finished tapestries, kept behind the closed doors of the workshop, were not for public display. The Grape Harvest or Autumn formed part of the fifth series of tapestry designs destined for the dining room of the palace of the Prince of Asturies – that is, the Palace of Pardo, home of the future Charles IV and his wife, Maria Lousia of Parma. This image represents one of the four seasons. The paintings served as models for the weavers, whose luxurious tapestries included silver and gold thread. The theme of the seasons was often used to decorate Rococo dining halls. Goya made the work his own by converting allegories into bucolic scenes representing different times of year. The harvest is adopted as the symbol of autumn.

Like the rest of the series, this painted model shows Spain as a happy, nonchalant idyll. This was far removed from the image, spread by the Romantics, of Spain as a country of cruel passions and ferocious religion. While the harvest takes place in the background, the vine branches at the feet of the nobleman underline the sensual character of his offering (the real subject of the composition). The peasant girl, outlined against the sky, carries a basket full of grapes on her head: a sort of still life emblematic of the harvest season. Unusually for Goya, this painting’s chief protagonists are not common people.

VINEYARDS - 15th CENTURY to 19th CENTURY

VIEW OF ARCO Watercolor, Albrecht Dürer, 1495 - Musée du Louvre, Paris

AUTUMN (probably in Francfurt area, Germany) Marten van Valckenborch (attributed to), ca. 1590s - Private collection

VIGNA DEL CARDINALE MAURIZIO DI SAVOIA (VILLA DEL REGINA) Pieter Bolckmann (?), ca. 1670 - Venaria, Italy

VIEW OF DRESDEN FROM DRESDEN FROM THE LOESSNITZ HEIGHTS Johann Alexander Thiele, 1751 - Gemäldegalerie, Dresden, Germany / 4

VIEW OF DIJON FROM DAIX Jean-Baptiste Lallemand, 1792 - Fine Arts Museum, Dijon, France

A VERANDA OVERGROWN WITH GRAPE VINES Sylvestre Chtchedrine, 1828 - The State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

BRIDGES OF SAINT-CLOUD AND SEVRES Joseph Mallord William Turner, 1833 - Tate, London

ON THE MOSEL: BERNKASTEL, KUES AND THE LAND SHUT, GERMANY Joseph William Turner, ca. 1825/34 - Private colection

OBERWESEL AM RHEIN WITH THE RUINS OF SCHÖNBURG CASTLE Johann Heinrich Schilbach, 1832 - German National Museum, Nuremberg

BOAT SCENE ON THE RHINE NEAR BINGEN (Germany) Johann Baptist Bachta, ca. 1840 - Museum am Strom, Bingen, Germany

THE VINE Charles-François Daubigny 1860/63 - Birmingham Museum & Art Gallery, Birmingham, England

VUE DE SENS DEPUIS LES VIGNES Philip Gilbert Hamerton, 1863 Towneley Hall Art Gallery and Museum, Burnley, Grande-Bretagne

VIEW OF LIBOURNE VINEYARDS Antoine Heroult, ca. 1840/45 - Private collection

VINEYARDS IN THE SNOX, LOOKING TOWARDS THE MILL AT ORGEMONT (Argenteuil, France) Claude Monet, 1873 - MFA, Richmond, USA / 14

LANE IN THE VINEYARDS AT ARGENTEUIL (CHEMIN DANS LES VIGNES, ARGENTEUIL) Claude Monet, 1872 - Private collection

A VINEYARD WALK AT LUCCA (Tuscany, Italy) John Ruskin, 1874 - Lancaster University, UK

CELEYRAN, VIEW OF THE VINEYARD Henri de Toulouse-Lautre, 1880 - Toulouse-Lautrec Museum, Albi, France

THE MILL OF ALPHONSE DAUDET AT FONTVIEILLE (watercolour) Van Gogh, July 1888 - Private collection

HOUSES AND FIGURE Vincent Van Gogh, February 1890 Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia, PA, United States

OLD VINEYARD WITH PEASANT WOMAN (Auvers, watercolour and oil) Vincent Van Gogh, May 1890 - Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, Netherlands

VINEYARDS AT AUVERS Vincent Van Gogh June 1890 - St Louis Art Museum, Missouri, United Sates / 21

HOUSES AT AUVERS Vincent Van Gogh, June 1890 Toledo Museum of Art, Toledo, OH, United States

MEMORY OF EVENING II or THE VINEYARD AT LE PECQ Maurice Denis, 1890 - Private collection

VINEYARD László Mednyánszky 1890/95 - Hungarian National Gallery, Budapest, Hungary / 24

VINEYARD László Mednyánszky, 1890/95 - Slovak National Gallery, Slovakia

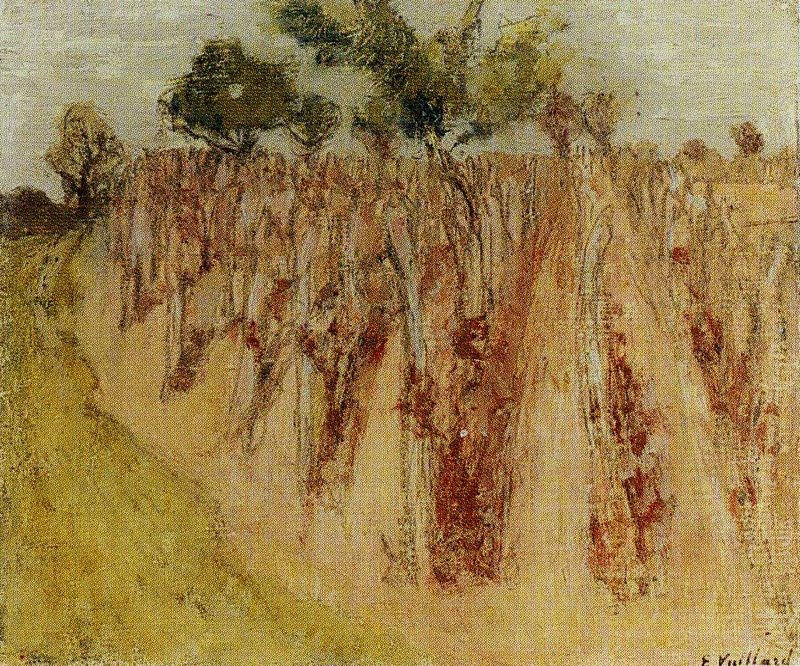

VINE IN VILLENEUVE-SUR-YONNE Edouard Vuillard, ca. 1897/99 - Private collection

WALKING IN THE VINEYARD Edouard Vuillard ca. 1897/99 - Los Angeles County Museum of Art, CA, United States

> Click on the icons for a closer look at the artworks

4. Vineyards on the slopes of Loessnitz with Dresden in the background.

14. Le moulin d’Orgemont était situé à un kilomètre de la maison d’Argenteuil, dans la banlieue parisienne, où Monet a vécu de 1871 à 1878. La scène peut être datée avec précision, une légère chute de neige s'étant produite en février 1873.

21. Vineyards with a View of Auvers was painted (oil) in 1890, while the artist was receiving treatment from Doctor Gachet.

24. Il n'était pas rare à cette époque de planter des arbres entre les plants de vigne. De nos jours, les agroforestiers s'imposent dans de grands domaines viticoles (à Saint-Emilion, Reims, Vosne-Romanée) et font de même. Les arbres apportent de l'ombre et limitent le déssèchement des sols, ils limitent les températures excessives par évaporation de l'eau. Les arbres se révèlent également comme un piège à carbone atmosphérique.

VINEYARDS - 20th CENTURY

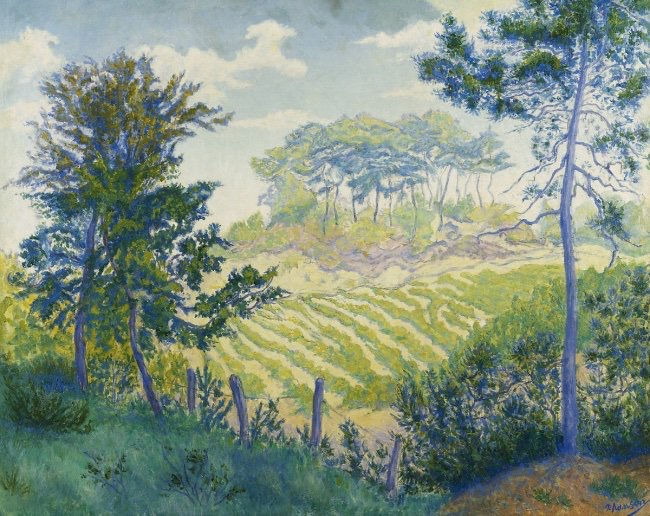

VINEYARDS UNDER THE PINES (LES VIGNOBLES SOUS LES PINS) Paul Ranson, 1896 - Private collection

THE VINES Paul Ranson, ca. 1902 - Private collection

VINE Kees Van Dongen, 1905 - Musée national Picasso, Paris

VINEYARDS IN SPRING (VIGNES AU PRINTEMPS) André Derain, 1904 -1905 - Kunstmuseum, Basel, Switzerland

LAKE GENEVA SEEN FROM CHEXBRES [Lavaux], Ferdinand Hodler 1984 - Cantonal Museum of Fine Arts, Lausanne, Switzerland

THE VINEYARD AT CAGNES (LES VIGNES A CAGNES) Auguste Renoir, ca. 1908 - The Brooklyn Museum, New York / 5

ALOE BLOSSOM, CAPE CANAILLE (close to Cassis) Henri Manguin, 1913 - Private collection

STEIN ON DANUBE WITH TERRACED VINEYARDS Egon Schiele, 1913 - Private collection

CONVENT OF THE CAPUCINS IN CERET (France) Jean Hyppolyte Marchand, 1916 - Moder Nart Museum, Céret, France

LANDSCAPE IN VERNON Pierre Bonnard, 1915 -Private collection / 10

LANDSCAPE AT SUNSET, LE CANNET Pierre Bonnard, 1927 - Kunsthaus, Zurich, Switzerland

LANDSCAPE, NICE (PAYSAGE, NICE) Henri Matisse, 1919 - The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

VINES AND OLIVE TREES, TARRAGONA Joan Miro, 1919 - The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York / 13

THE DEVIL'S VINEYARD Harvey Dunn, ca. 1918 - South Dakota State Univ. Art Mus., United States / 12

LANDSCAPE IN NAHETAL Erich Heckel, 1930 - Private collection

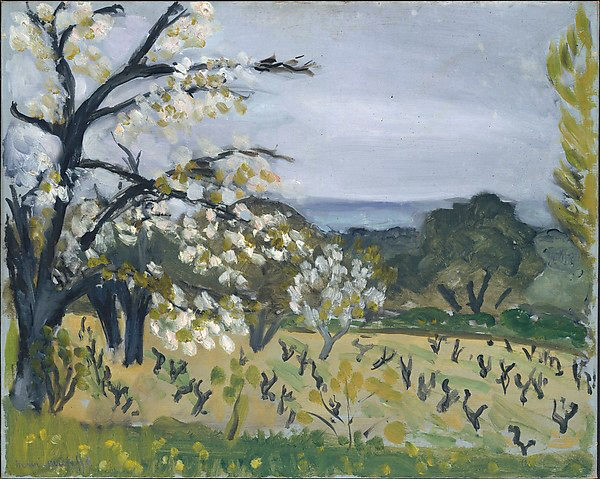

VINEYARDS IN AUTUMN (France) Henri Martin, ca. 1925/30 - Private collection

VINEYARDS AT THE FOOT OF ZOBOR (Slovakia) Karol Pongrácz, 1930/40 - Slovak National Gallery, Bratislava, Slovakia

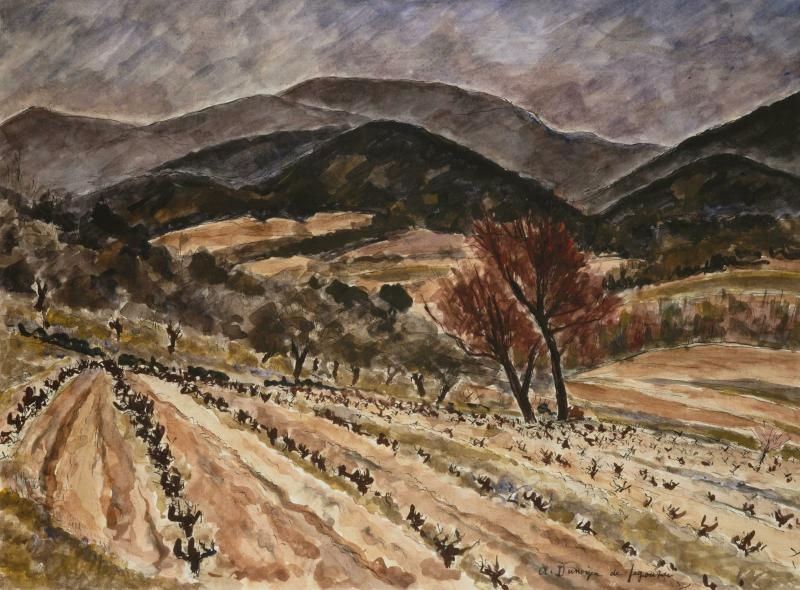

SAINT-TROPEZ BAY (France) André Dunoyer de Segonzac, 1929 - Private collection

LANSCAPE IN PROVENCE (France) André Dunoyer de Segonzac, after 1935 - Pompidou Center, Paris

> Click on the icons for a closer look at the artworks

5. In 1888, Renoir’s mistress Aline Charigot, with whom he had three children and who would later become his wife, convinced the artist to explore his birthplace: the village of Essoyes, in the Aube region of Champagne. At this time, the Barrois was a region dominated by so-called still wines (not sparkling or effervescent). The couple bought a house there, and visited every summer for the rest of their lives. Renoir counted many friends among the local vineyard owners – “I liked being with the vignerons because they are generous” – and appreciated the colours of the region and its vines. In 1903, he found more vines at Cagnes-sur-Mer, where he moved in with his family as the climate was thought to be better for his health. In 1907, Renoir acquired the Collettes domain, situated on a hillside to the east of Cagnes. Aline Charigot had a house built there, where Renoir would spend his twilight years from 1908 to 1919.

It was here that Renoir painted this work the moment he moved in. He depicts his wife managing the land, notably the olive trees and vines. In this arid area, the vine is bush-like; the grapes are still (but not for much longer) being grown by layering, without alignment or trellising, growing anarchically. There is little uprooting here: the vines are renewed with provignage, meaning that the shoots are simply laid on the ground until they take root.

10. Bonnard had had vines planted in the garden of his home in Vernon, according to the property’s current owner.

12. In April 1917, the US Congress voted to “recognize the state of war between the United States and Germany”. US forces arrived in France in June 1917. Along with seven other artists, Harvey Dunn was sent to the Front as an American army correspondent. Their mission was to record the conditions and actions of the Allied troops. Dunn was affected to the 16th Infantry Regiment. On 18th July 1918, the regiment took part in the Battle of Soissonnais, an Allied counter-attack in response to the German “Friedsturn” offensive in the Reims region three days earlier – more commonly known as the Fourth Battle of Champagne. The Allies recovered most of the ground lost to the Germans since late March. The battle was extremely bloody: the Allies lost 125,000 men (including 12,000 Americans), while the Germans lost 168,000. It seems likely that Dunn’s The Devil’s Vineyard is a record of this battle. Although conditions have been hellish, the painting gives off a kind of tragic calm. Soldiers lie on the ground while vine supports hold up a tangled mess of barbed wire and trapped guns.

13. Miró passera ses étés pendant 65 ans à travailler dans la ferme familiale de Montroig del Camp, en Catalogne, non loin de Tarragone.

« Montroig, disait-il, c’est comme une religion pour moi, c’est l’impact préliminaire, primitif auquel je reviens toujours. Montroig m’insuffle un grand enthousiasme, et je peins comme un fou. ». Cette toile éclate de vie et de couleurs et un luxe de détails illustre l’amour de Miró pour les petites choses, pour « l’infime ».

VINES AND "LAKE GENEVA" (LAC LÉMAN) Max Pechstein, 1925 - Private collection

CHURCH AND VINEYARDS IN GRIZZING (Döbbling, Vienna, Austria) Carl Moll, 1930/35 -Leopold Museum, Vienna, Austria

VINEYARD IN THE SUN Gulio Ripera, 1955 - Mantova Museo Urbano Diffuso, Mantova, Italy

VINEYARD ON THE HILL Raymond August Mintz, 1956 - Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

VINES, CAMBLES (near Bordeaux, right bank) Charles Cante, 1960/70? - Private collection

VINEYARDS Godofredo Ortega Muñoz, 1967 Fundación Banco Santander, Boadilla del Monte, Spain

THE VINEYARDS Olga Konoschuk, 2005 - Private collection

VINEYARDS II Olga Konoschuk, probably 2005 - Private collection

VINEYARD Aleksander Britsev, 2009 - Private collection

VINEYARD IN BARJAC Anselm Kiefer, 1976? - Private collection

THE EVENING OF ALL DAYS, THE DAY OF ALL EVENINGS (ALLER TAGE ABEND, ALLER ABENDE TAG) Anselm Kiefer, 2014

AUTUMN VINEYARD Igor Shipilin, 2014 - Private collection

BEFORE THE GRAPE HARVEST

MARCH, PRUNING Mural painting, 14th century - Saint-Etienne de Paulnay Church, Indre, France

ALLEGORY OF MARCH: TRIUMPH OF MINERVA (lower layer detail) Francesco del Cossa, 1476/84 - Palazzo Schifancia, Ferrara, Italy / 2

THE LABOURS OF THE MONTHS, MARCH, PRUNING Anonymus, 1520/30 - The National Gallery, London

LANDSCAPE WITH PEASANTS WORKING IN A VINEYARD Jan Abrahamsz Beerstraaten (1622-1666) - Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg

IN THE VINEYARD Jean-François Millet, 1852/53 - Museum of Fine Arts (MFA), Boston, United States

TRAINING VINES Jean-François Millet, ca. 1860/64, Pastel - Museum of Fine Arts (MFA), Boston, United States

VINEYARD LABOURER RESTING Jean-François Millet 1869, pastel - Mesdag Collection, The Hague, The Netherlands

TILLING IN THE VINEYARD (LE LABOUR DANS LES VIGNES) Toulouse-Lautrec, 1883 - Private collection

WOMEN TYING UP THE VINE Henri-Edmond Cross 1890 - Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid, Spain

SOIL TRANSFER Gustave Jeanneret ca. 1890 - Vine Museum, Boudry, Neuchatel County, Switzerland

PRUNING VINES Gustave Jeanneret ca. 1890 - Vine Museum, Boudry, Neuchatel County, Switzerland

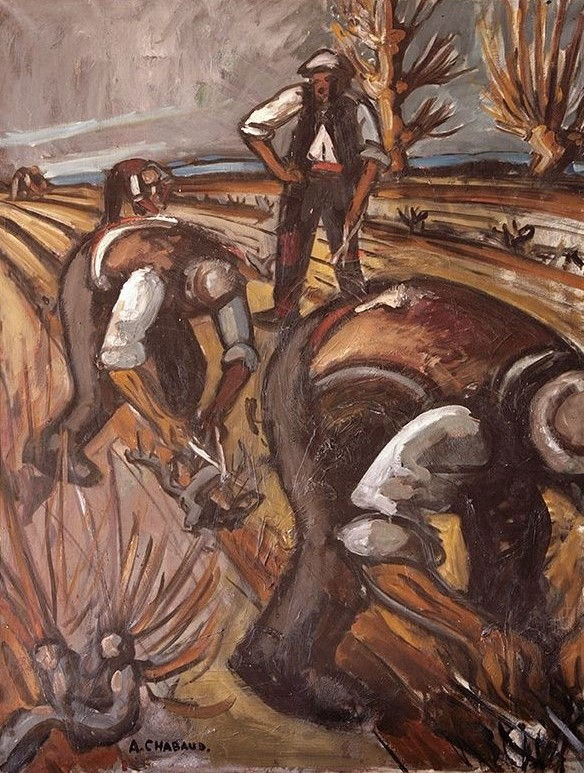

WORKERS PRUNING VINES Auguste Chabaud, 1925 - Musée Auguste Chabaud, Grameson (Provence), France

WORKERS PRUNING VINES Auguste Chabaud

TILLING, PREPARING VINES IN QUERCY (detail) Henri Martin, 1929 - Hôtel de Préfecture du Lot, Cahors, France

TREATMENT WITH SULFATE Henri Martin, ca. 1925 - Private collection

PRUNING THE VINES Josef Herman, 1952 - National Museum Wales / 16

DIGGING ROOTED VINES Josef Herman, 1949 - York Art Gallery, York, England

PRUNING VINES (in Provence, France) Jill Steenhuis, 2008

> Click on the icons for a closer look at the artworks

2. Palazzo Schifanoia, one of the masterpieces of Italian palace architecture, was decorated with a series of allegorical frescoes symbolizing the months.

16. It is in vineyards near La Rochepot, on Côte de Beaune, Burgundy.

GRAPE HARVEST - 15th CENTURY to 18th CENTURY

OCTOBER Unknown Master, Italian, ca. 1400, Fresco Eagle's Tower, Castello del Buonconsiglio, Trent, Italia

AUTUMN (GRAPE HARVEST) Francesco Bassano ca.1585/90 - Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria

AUTUMN, MOSES RECEIVING THE TEN COMMANDMENTS Jacopo Bassano, c. 1576 - Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austrian / 3

AUTUMN WITH THE GRAPE HARVEST Lucas van Valkenborch, 1585 - Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria

WINEGROWER Jacob Gerritsz Cuyp, 1628 - The Hermitage, St Petersburg, Russia

AUTUMN, MARKET SCENE IN THE HEART OF A VILLAGE Sebastian Vrancx, 1620/22 - Private collection / 6

THE GRAPE HARVEST David Teniers the Younger, 1640-43 - Private collection

GRAPE HARVEST Jan de Momper, 1660s - Akademie der bildenden Künste, Vienna, Austria

GRAPE HARVEST Jean-Baptiste Pater, ca. 1720 - Private collection

A FÊTE CHAMPÊTRE DURING THE GRAPE HARVEST Jeab-Baptiste Pater, ca. 1730/33 - Dallas Art Museum, TX, USA

GRAPE HARVEST or AUTUMN (LES VENDANGES ou L'AUTOMNE) Noël Hallé, 1776 - Château du Petit Trianon, Versailles, France

AUTUMN, GRAPE HARVEST IN SOORENTO Jacob Hackert, 1784 - Wallraf-Richartz-Museum, Cologne, Germany

> Click on the icons for a closer look at the artworks

The fruit of a year’s hard labour, the harvest was a key moment that had to be chosen carefully: we “reap what we sow”. It was traditionally a period of celebration.

3. This painting is part of a series depicting The Four Seasons. They are derived from a series first designed by Jacopo Bassano around 1574. The series proved extremely popular and a number of versions were created within the Bassano family workshop. Francesco continued to produce the scenes in the later 1570s and 1580s. In Autumn, the rich abundance of the harvest is illustrated. On the far left of the composition, Moses receives the two stone tablets containing the Ten Commandments on Mount Sinai. This was a popular iconography during the Renaissance and it was not unusual to include the detail within a larger genre scene such as the harvest.

6. The foreground is dominated by townspeople buying and selling apples and finches and, to the right, a man bringing grapes to be pressed for wine - all autumnal activities.

GRAPE HARVEST - 19th CENTURY

THE FESTIVAL OF THE OPENING OF THE VINTAGE AT MÂCON, FRANCE Turner, 1803 - City Art Gallery, Sheffield, United Kingdom / 1

FIGURES AND ANIMALS IN A VINEYARD John Frederick Lewis ca. 1829 - Yale Center for British Art, New Heaven, Connecticut, US / 2a

FIGURES AND ANIMALS IN A VINEYARD (detailed) John Frederick Lewis ca. 1829 - Yale Center for British Art, New Heaven, Connecticut, US / 2b

LANDSCAPE NEAR TIVOLI WITH VINTAJERS Karoly Marko the Elder, 1846 - Magyar Nemzeti Galéria, Budapest, Hungary

GRAPE HARVEST Nicola Palizzi, 1847 - Private collection

HARVEST IN FRONT OF CHILLON CASTLE. GENOVA LAKE Swiss School, mid 19 th century - Private collection

GRAPE HARVEST IN MEDOC Clément Boulanger, 1830 - Fine Arts Museum, Bordeaux, France

THE VINTAGE IN THE CLARET VINEYARDS OF THE SOUTH OF FRANCE ( Haut Médoc) Thomas Uwinsn, 1847/48 - Tate Britain, London

THE VINTAGE IN CHATEAU LAGRANGE (detailed) Jules Breton, 1864 - Joslyn Art Museum, Omaha, Nebraska, United States

HARVEST IN BURGUNDY Charles-François Daubigny, 1863 - Musée d'Orsay, Paris

GRAPE HARVEST NEAR VAC Agost Canzi, 1859 - Magyar Nemzeti Galléria, Budapest, Hungary

GRAPE HARVEST ON THE BANKS OF THE SEINE RIVER, IN SURESNES Constant Troyon, 1856 - Musée d'Orsay, Paris

THE GRAPE HARVEST AT SÈVRES Camille Corot, 1865

THE GRAPE HARVEST (At Damvillers) Jules-Bastien Lepage, 1880 - Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

PARCEL IN LANGUEDOC VINEYARDS Edouard Debat-Ponsan, 1886 - Fine Arts Museum, Nantes, France

VINEYARDS IN LIVERMORE (California) Unknown master, 1870s or 1880s - Private collection

THE AUTUMN (GRAPE HARVEST ALLEGORY) Alfons Mucha, 1886 - Private collection

GRAPE HARVEST Francesco Gioli, 1890 - The Uffizi Galleries, Florence, Italy

GRAPE PICKERS AT LUNCH Auguste Renoir ca. 1888 - Armand Hammer Coll., Los Angeles County Art Museum, CA

THE GREEN VINEYARD Van Gogh, 1888 - Rijksmuseum Kröller-Müller, Otterlo, Netherlands / 19

RED VINEYARDS AT ARLES, MONTMAJOUR V. Van Gogh, 1888 - The Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow, Russia / 20

GRAPE HARVEST AT ARLES or HUMAN ANGUISH Paul Gauguin, 1888 - Ordrupgaard, Copenhagen, Denmark / 21

THE VINTAGE (VAR) Henri-Edmond Cross, ca. 1891/92 - Private collection

GRAPE HARVEST IN PROVENE (Southeastern France) Etienne Martin, ca. 1895 - Fine Arts Museum, Dijon, France

> Click on the icons for a closer look at the artworks

1. Turner traveled through Macon in Burgundy during the grape harvest in 1802. This impressive painting supposedly depicts the festival which accompanied the harvest close to the Saone river, but is in fact a view of the Thames from Richmond Hill in Surrey.

2. Vintajers pause from gathering grapes to join a seated Capuchin friar who leads them in reciting from his breviary.

19. Van Gogh painted two landscapes featuring vines in oils – The Green Vineyard and Red Vineyards – during his period in Arles, where he lived from February 1888. Van Gogh went South in search of light and colour. On 3rd October, in one of his many letters to him, he told his brother Theo that he had finished the painting: “I have an extraordinary fever for work these days, at present I’m grappling with a landscape with blue sky above an immense green, purple, yellow vine with black and orange shoots. Little figures of ladies with red sunshades, little figures of grape-pickers with their cart further liven it up.” The scene is described in minute detail. The harvest seems to have got off to a good start, although the pace is slow.

20-21. The other vineyard painting, Red Vineyards at Arles, Montmajour, is one of Van Gogh’s best-known works (Find out more >>). Gauguin joined Van Gogh in the South at the end of October. In another letter to Theo, dated 3rd November, Van Gogh recounts a walk to Montmajour and Trébon, several kilometers from Arles and not far from the Fontevielle windmill, which he had taken with Gauguin the weekend before, the 28th October, at sunset: “We saw a red vineyard, completely red like red wine. In the distance it became yellow, and then a green sky with a sun, fields violet and sparkling yellow here and there after the rain in which the setting sun was reflected." The result of this colorful walk? In his letters, Van Gogh is Gauguin’s record-keeper. On the 3rd November, he relates: “At the moment he’s working on some women in a vineyard, entirely from memory, but if he doesn’t spoil it or leave it there unfinished it will be very fine and very strange”. On the 10th November, he announces that “Gauguin has finished his canvas of the women picking grapes”. If Gauguin’s memory of the vineyard’s colours was spot-on, other details are less exact: the women in his painting are wearing headdresses from Brittany! Sardonically, Van Gogh adds: “I haven’t seen the Breton things...” Gauguin describes the painting to Emile Bernard: “The red vines form a triangle. To the right, a Breton woman, from Pouldu, in black. Two women bending over, in blue dresses and black corsages. In the foreground, a little peasant girl with red hair and a green skirt. Thick lines full of colour, the knife laid very thick on the rough canvas. It’s an effect I took from the vines in Arles. I put Bretons in the picture. Not very accurate, but who cares?”

By comparing Van Gogh’s Red Vineyards to Gauguin’s Grape Harvest at Arles (Human Anguish), we can see significant differences in approach and attitude. Gauguin doesn’t give two hoots for reality, explaining that “it’s an effect I took from the vines in Arles… not accurate, but who cares?” His aim is to communicate a lived experience, something he achieves by rearranging the image to juxtapose the Breton figures and the southern vines, transfiguring the landscape. In reality, the harvest in Province had taken place long before the execution of the painting, on the 20th September. There would have been no one in the bare vineyard at the time of painting. The two artists worked from memory and if they were accurate in their representation of the bright reds and yellows of the autumnal vine leaves (typical of the vineyards in late October, after the harvest) they let their imaginations run wild for the rest. These compositions clearly show that some painters tell a story of wine - their own - rather than recounting its history.

GRAPE HARVEST - 20th CENTURY

WINE HARVEST IN THE TYROL Peder Severin Krøyer, 1901 - Grohmann Museum, Milwaukee, United States

GRAPE HARVEST Dora Hitz, bef. 1911- Stiftung Stadtmuseum, Berlin, Germany

CARRIERS (GRAPE HARVEST) Natalia Gontcharova, 1911 - Pompidou Center, Paris

FEET PRESSING GRAPES (HARVEST) Natalia Gontcharova, 1911 - Pompidou Center, Paris

SMALL HARVEST Max Slevogt, 1913 - Slevogt-Galerie Schloss Ludwigshöhe, Edenkoben,

GRAPE HARVEST Augusto Giacometti, ca. 1915 (?) - Private collection

THE GRAPE HARVEST Henri Martin, ca. 1920 - Private collection

AUTUMN or GRAPE HARVEST (L'AUTOMNE ou LES VENDANGES) Pierre Bonnard, 1912 - Pushkin Museum, Moscow, Russia

GRAPE HARVEST Pierre Bonnard, 1926 - The Phillips Collection, Washington

VINE AND WINE ALLEGORY (ALLÉGORIE DE LA VIGNE ET DU VIN) Jean Dupas, 1925 - Musée d'Aquitaine, Bordeaux, France (Click for a closer look at the artwork) / 10

HARVEST IN VALAIS [Switzerland] Alexandre Blanchet, 1917 - Kunst Museum Winterthur, Winterthur, Switzerland

GRAPE HARVEST Emile Othon Friesz, 1924 - Musée des Beaux-arts, Grenoble, France

LAND OF THE VINEYARDS Alice Bailly, 1924 - Musikkollegium, Winterthur, Switzerland

VINTAGE AT MARTILLAC Georges de Sonneville, 1927 - Musée des Beaux-arts, Bordeaux, France

WINE ALLEGORY Francois-Maurice Roganeau, 1938 - Bourse du travail, Bordeaux, France

HARVEST Sketch for a mural painting Roger Chapelain-Midy, 1938 - Fine Arts Museum, La Rochelle, France

GRAPE HARVEST AT CADAQUES Rafael Durancamps i Folguera 1939-1950 ? - Colección Carmen Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid

THE WINE HARVEST (LES VENDANGES) Marc Chagall, 1954 - Pompidou Center, Paris

VINEYARDS IN THE AUTUMN Josef Herman, 1957 - Private collection

THE GRAPE HARVEST, BORDEAUX Josef Herman, 1950s? - Private collection

GRAPE PICKERS IN BURGUNDY Josef Herman, 1968/72 - Private collection

GRAPE HARVEST (COMPOSITON 405) Roger Bissière, 1958 - Pompidou Center, Paris

> Click on the icons for a closer look at the artworks

10. Cette peinture monumentale (306 x 840 cm) célèbre la plus emblématique des ressources économiques de Bordeaux et de sa région : la vigne et le vin. Des annotations de la main de l’artiste sur un dessin préparatoire (une gouache sur papier) indiquent le nom des allégories composant cette longue frise de personnages. De gauche à droite sont évoqués : la joie, la force, l'esprit, l’appel, le vin, les hommes (en bas au centre), l'invitation, les vendanges, la sorcière préparant le feu pour l'alambic, la divine liqueur et enfin l'Alcool. Elle fut réalisée à l’occasion de l’exposition internationale des arts décoratifs et industriels de Paris pour orner la tour de Bordeaux. Elle devait avec trois autres grands décors (L’Agriculture de Jean Despujols, La Forêt landaise de François-Maurice Roganeau, Les Colonies de Marius de Buzon) glorifier les principales ressources économiques de Bordeaux et de sa région. (Source : Musée d'Aquitaine, Bordeaux)

LOOKS CAN BE DECEIVING

Le titre de cette œuvre espagnole Paysage avec une vigne (La Paisaje con una vid, Tomás Hiepes, 1645, Musée du Prado, Madrid) est trompeur. En réalité, le Prado nous indique que Hiepes a eu recours à l’un des thèmes les plus fréquents des débuts de la peinture de natures mortes en Espagne : le raisin. Mais au lieu de représenter les grappes seules ou à l’intérieur, il les montre dans leur espace naturel, la vigne, à laquelle elles sont comme suspendues. Ce gros plan sur un pied de vigne bouleverse les catégories en plaçant cette toile apparemment à la fois dans deux genres différents : celui des natures mortes et celui des paysages. Mais la nature morte est comme plaquée sur le paysage situé à l'arrière-pan. Il donne à ce tableau une valeur hautement décorative, à laquelle participe également l'escargot, bien qu'il soit lui placé au premier plan.

La maîtrise avec laquelle les raisins sont peints corrobore l’éloge que Marcos Antonio de Orellana a dédié au XVIIIe siècle à "une corbeille pleine de raisins, dont les grains diaphanes et transparents, avec leurs branches, pouvaient tromper les oiseaux."

This Renoir painting has been often reproduced and copied. It is known by many titles in English and French, all of which evoke the grape harvest. For many years it was displayed in the Washington National Gallery of Art under the title The Vintagers. Upon closer examination, one might wonder where the scene is set, given the astonishing fact that no vines appear in the painting. What was Renoir doing during the 1879 harvest season? He was holidaying less than three kilometres from Berneval, near Dieppe, as a guest of his new friends Marguerite and Paul Bérard at the Chateau de Wargemont, Derchigny-Graincourt. This area had never had vines, even before the arrival of phylloxera! Not only that, but there have been no vines in Normandy since the end of the eighteenth century!

Continuing our research, we learnt that this painting had been lent to the National Gallery of Ottawa (Canada) in 2007 for an exhibition on the landscapes of Renoir. It was displayed under the name The Mussel Harvest – quite a change from its previous title. All became clear: the figures are fishermen climbing up the beach, following a path along one of the ravines that characterize so well this part of the French Normandy coast. This is well corroborated by both the Berneval parish website and Mussel-Fishers at Berneval, which Renoir painted during the

same visit. The fisherwomen’s baskets resemble those in the other painting. Mussel-fishing was one of the area’s primary activities. So why was The Mussel Harvest misnamed for so long? There was probably some confusion (before the purchase of the painting by the American tycoon Adolph Lewisohn in 1921) between the words harvest and harvesters, as these terms can be applied not only to the fields, but also to the vineyards and the sea, depending on the context.

LE VIGNOBLE BORDELAIS VOISINE AVEC LES AUTRES ACTIVITES AGRICOLES

Cettre œuvre de Jean Despujols (L'Agriculture, 1925, 306 x 840 cm - Musée d'Aquitaine, Bordeaux), proche du style art déco très vivace dans l’entre-deux-guerres, est habitée par des figures allégoriques disposées à la manière d’une frise antique. Elle exalte la prospérité de l’agriculture régionale. La composition d’une grande lisibilité montre un paysage soigneusement agencé en arrière-plan et les différentes activités agricoles qui font la richesse du terroir aquitain. Les rangs de vignes serrés et alignés évoquent un vignoble très ordonné.

FROM VINEYARD TO GRAPE HARVEST IN MEDIEVAL ILLUMINATIONS

PRUNING IN MARCH Heures de Catherine de Médicis, 1500?-1550? BnF, Paris

AUTUMN Tacuinum Sanitatis, ca. 1390 - Munich

GRAPE HARVEST Heures à l'usage de Cluny, ca. 1500 - BM, Amiens, France

SEPTEMBER Bréviaire de Grimani, ca. 1510/20 - Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana, Venice, Italy

> Click on the icons for a closer look at the artworks

A pictorial technique similar to that of frescoes or miniatures, illuminations were very popular during the Middle Ages. Done by hand, illuminations decorated or illustrated texts, usually on handwritten manuscripts. Until the 12th century, manuscripts were copied out in religious settings, such as abbeys, where they were used to support prayer and meditation. From the 13th century, private artisans began to produce literature for the secular market. This was due to the greater literacy that had resulted from the growing university and administrative sectors.

Find out more: Wine in Illumination, From Vineyard to Port >>

WINE AND THE ARTS: SCULPTURE IN SACRED ART

Polychrome on a capital 12th Century - Romanesque church (Puy-de-Dôme), France

Grape harvest and stomping Portal, 3rd archivolt, calendar, September between Libra and Scorpio, 1130/35 - Saint-Lazare Cathedral, Autun, France

Zodiac and the Labors of the Month, March Peasant pruning the vine Narthex central tympanum, 1120/30 - Vezelay Basilic, France

Zodiac signs singing Labors of the Months Saint-Firmin portal, 1220/30, Amiens Cathedral, France

> Click on the icons for a closer look at the artworks

The ‘Muses’ companion’, wine is present across the artistic spectrum, be it in literature, music, decorative or fine arts. Wine is an essential witness to our social and cultural history. Although The Virtual Wine Museum is mainly concerned with painting at present, some examples drawn from other artistic formats permit us to illustrate the universal role of wine, to ‘bear witness’ to it. A few examples from religious art: 1/ Marauders in the Vine*, a 12th-century painted capital in the Romanesque abbatial church of Saint-Pierre de Mozac, Puy-de-Dôme, France. 2/ Libra and September, zodiac calendar, third archivolt on doorway, 1130/35, Autun Cathedral Saint-Lazare, France. 3/ Zodiac and monthly tasks, March, Pruning. Peasant pruning a vine, narthex central tampanum, 1120/30, Vézelay Basilica. 4/ Grape Harvest, one of a series of quatrefoil medallions showing an agrarian calendar connecting the signs of the zodiac with seasonal tasks, left foundation of the Saint-Firmin doorway, 1220/30, Amiens Cathedral, France.

* Marauders in Vineyards (title attributed by INRAP, Institut National de Recherches Archéologiques Préventives) are shown harvesting grapes that do not belong to them, before the official start of the harvest season.

Find out more: Vine and the Wine in Sculpture >>

GALLERIES FROM VINEYARD TO PORT

> Wine and Painting > From Vineyard to Port > From Vineyard to Harvest